To help the library continually improve, please use the form below if you wish to give feedback or suggestions about this guide.

The databases you select will depend on your research question and discipline. The Databases A-Z page can be used to find the key databases in your discipline by using the All Subjects drop down box, and selecting your discipline area.

The majority of reviews will search primary databases, which include published articles and original research. Some are discipline specific, such as CINAHL, and others such as Scopus and Web Of Science are multidisciplinary and cover a wide range of topics. You may also want to search in secondary databases which include systematic reviews and other evidence based material, such as the Cochrane Library.

When you search, only search in one database at a time as you may need to report how many articles you found in each.

Depending on your review type and topic, you may want to search for grey literature as well. Grey literatureis information published by governments, academics, business or industry that is not driven by commercial publication. Resources of sufficient quality, such as theses, pre-prints, reports, research registers or conference proceedings may be housed in repositories or libraries.

The benefits of including grey literature can be:

However, it can be more challenging to find, as it is often not indexed in centralised databases. You can find grey literature in publicly accessible databases, by checking reference lists of relevant journal articles, or by advanced Google searches. The Grey literature subject guide has detailed information and instructions on finding grey literature.

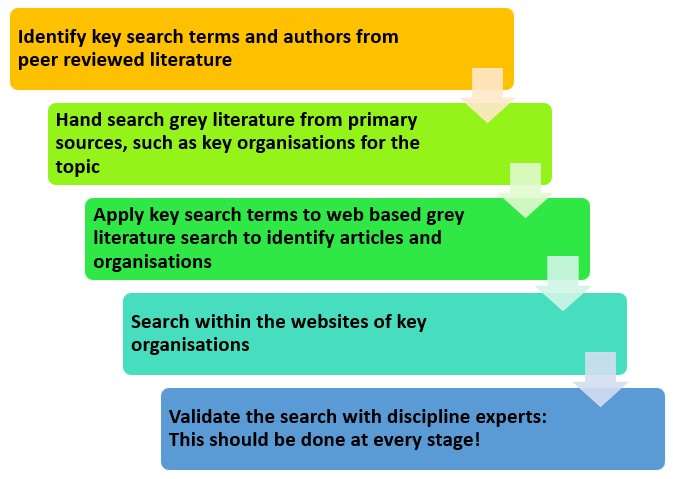

A suggested process for searching for grey literature is:

If you choose to include pre-prints, be aware that they will not have gone through peer review yet, and as such would need to be carefully scrutinised for quality and risk of bias. Additionally, pre-print servers may not have the ability to conduct complex searches. Some common pre-print servers are:

It is recommended the reference lists of relevant articles are also searched for additional studies. Depending on the number of results found, you may choose to look at the references of all studies found, or to only examine the references from studies to be included after the screening process has been done. If there appears to be relevant studies in a reference list that were not retrieved in your search, examine why this has occurred. You may have missed a key search term, or not searched in the source they are in.

You may also decide to hand search key journals in your discipline for relevant studies that have not been located in the database search, or to check publications of key authors.

There are a number of citation tracking tools in the box below that can assist in finding articles from reference lists, newer articles citing your included articles, and other key papers and authors.

When you are conducting a systematic review it is very important to document the details of your search including:

Source: Monash University and University of Manitoba

Systematic searching takes many hours of hard work with trial end error as you refine your searches. So documentation will:

Source: Monash University

The research question will guide your search. Each concept in your question will have a set of search terms that you will combine to create a search. If you have used a framework, such as PICO, you do not necessarily need to include all concepts in your search.

The first step is to identify all the alternative terms that authors may use for each concept. You will need to consider:

The initial limited search will help to locate terms that authors use when writing about the topic. It is a good idea to keep a record of the terms you find and use, so that you can alter and keep track of them. One way to do this is in a table. You can arrange it to best suit your research question, and edit terms to include any truncation or proximity operators used. You can test your terms in various databases, and see if they bring back relevant results.

| Concepts | University students | Stress | Assessments |

| Key words | Higher education student, tertiary education student, college student, undergraduate | Worry, anxiety, pressure, nervous | Assignments, exams, evaluations |

The second step is to find the index terms for each concept. These are keywords added to the article by the publisher or database and are also known as thesaurus terms, descriptors, subject headings, topic headings, and index headings. They allow you to find articles about a topic, regardless of what terms the author has used. For instance, even if the author only uses decubitus ulcers in an article, the standard index term pressure ulcers will be added by the publisher or database.

Index terms can be very different across each database, so you will need to find them in each database you search. Use the scope notes to see what the database means by each index term to make sure it matches the concept you are searching for. Additionally, when adding index terms to your search, each database may have different 'codes' used to distinguish them from general keywords. See the table below for an example of how CINAHL codes index terms.

Many databases allow you to choose Explode or Focus (sometimes called Major Concept) on an index term. Explode will find the index term, as well as anything else included underneath. This is useful for review articles, as you want to find anything potentially relevant. Focus (or Major Concept) will find articles where the index term is an important part of the article. This can be useful for when you want a quick result, but in a review search, it can mean potentially relevant articles are missed.

You can add the index terms to your search record, including the field code (this is usually different for each database). The following terms are from CINAHL. In this example, there is a plus sign after the term Stress to indicate it can be 'exploded' to include other sub-terms that sit underneath. So this will also find articles with the index terms Compassion Fatigue, Financial Stress and Professional Burnout that sit underneath the term Stress.

| Concepts | University students | Stress | Assessments |

| Key words | Higher education student, tertiary education student, college student, undergraduate | Worry, anxiety, pressure, nervous | Assignments, exams, evaluations |

| Index terms | (MH "Students, College") | (MH "Stress+") | (MH "Student Assignments") |

Text mining is where digital apps or computers analyse words within texts. It can be useful when conducting a search for a review as it can analyse citations, help to identify concepts and terms or speed up search development.

In a review, you need to find all the possible articles that meet your criteria, so you will need to use some more advanced operators in your search. Often these are different for each database so you will need to check before running your search. The PDF below shows the operators used in the most common databases.

Truncation: This will find all variations from a word stem and is often an asterix. For example, search* will find search, searched, searching, searches.

Wildcards: This allows you to find different spelling of a word, and can be used for a single character or no character. The symbol varies considerably between databases, but in this example is a question mark. For example, colo?r will find colour and color, or minimi?e will find minimise and minimize.

Proximity operators: As the search needs to find all available sources, it is recommended to avoid phrase searching with quotation marks, eg. "internet search". Instead, use proximity operators: internet N4 search* (in an EBSCO database). This will find the words internet and search within 4 words of each other (in either direction). This is better than "internet search" because it will still find internet search, but it will also find internet keyword search, internet site search, searching the internet, and similar phrases.

Boolean operators are used to combine all the terms.

AND connects each different concept: university AND student AND assessment

OR connects alternative terms for the same concept: university OR higher education OR tertiary education

NOT excludes a concept but can remove relevant results, so use with caution! university NOT college

Add brackets around the similar terms so that the database knows which order to search for:

(university OR higher education OR tertiary education) AND (student OR learner) AND (assessment OR evaluation)

When applying limits, consider the potential risk of bias. Ask yourself why a particular limit such as a date range is required and record the justification.

You can apply limits either when you run each individual search line, or after you have combined the searches. This is a personal preference, although if you apply them for each line, you need to remember to do so each time! Common limits in reviews include a date range, language of the article, or geographic area. Some reviews are limited to particular study types or populations. The limits will depend on the inclusion and exclusion criteria set in the protocol.

Often there are more limits available in the advance search screen, such as study types or age range. However if you only need common limits you can easily apply them in the results screen. Be aware though, that using limits such as study type runs the risk of not finding relevant studies if indexing is inaccurate. It may be more comprehensive to apply age limits when screening articles, or to include a study type as a search concept.

While it is possible to run your search all on one line, it is recommended that you build your search by searching for each element separately and then combine them using Boolean operators. This helps you easily identify if you have made any errors. Each database will look slightly different, so contact your liaison librarian or access the database's Help page for further assistance.

Make sure you use both keywords and index terms, applying any wildcards, proximity operators and truncation to the keywords. The following examples show line searches in EBSCO databases (Medline, CINAHL, etc).

For each concept, first search for the index terms, then the related keyword terms and combine with OR in the search history. You can search for each keyword term on a separate line if you prefer. This will find all of the results with those keywords or index terms about the first concept.

Then search for each of the other concepts in the same way. Finally, join all of the 'combined' lines (S1 OR S2) using AND. This will find results that have all of your search elements in them.

You will need to translate your search strategy when searching across different databases because the field codes, syntax, and subject terms may vary (Clark et al., 2020; Glanville et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2022; Wanner & Baumann, 2019). However, Polyglot is a useful tool developed by Bond University as part of a suite of systematic review tools and allows you to copy and paste a search strategy which is then translated for use across multiple databases. Bond University provides instructions for using Polyglot.

Citation tracking software is useful to find related articles, the references in articles, or newer articles that cite particular articles. It can be done towards the start of the search process to locate key papers, or once the selection and screening has been done to find articles cited by and that cite the included articles. Often PubMed records are used because it is an open access search platform. Some of these resouces require you to create a free account.

Search filters (sometimes called 'hedges') are pre-tested search fragments that you can include in your search strategy. They will find all articles of a specific type (methodology type, specific subject/discipline area, etc). Combine one or more search filters with your own topic search terms for more sensitive (wider coverage) searching. Here are some common sources for research filters (this is not a comprehensive list):

Clark, J. M., Sanders, S., Carter, M., Honeyman, D., Cleo, G., Auld, Y., Booth, D., Condron, P., Dalais, C., Bateup, S., Linthwaite, B., May, N., Munn, J., Ramsay, L., Rickett, K., Rutter, C., Smith, A., Sondergeld, P., Wallin, M., Jones, M., & Beller, E. (2020). Improving the translation of search strategies using the polyglot search translator: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 108(2), 195-207. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.834

Glanville, J., Foxlee, R., Wisniewski, S., Noel‐Storr, A., Edwards, M., & Dooley, G. (2019). Translating the Cochrane EMBASE RCT filter from the Ovid interface to Embase.com: a case study. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36(3), 264-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12269

Russell, F., Grbin, L., Beard, F., Higgins, J., & Kelly, B. (2022). The Evolution of a Mediated Systematic Review Search Service. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 71(1), 89-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2022.2029143

Wanner, A., & Baumann, N. (2019). Design and implementation of a tool for conversion of search strategies between PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE. Research Synthesis Methods, 10(2), 154-160. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1314